St. John’s Lutheran Church

24 December 2023 + Nativity of Our Lord

Luke 2:1-20

Rev. Josh Evans

To be perfectly honest: I never really cared for the Christmas Eve ritual of lighting candles and singing “Silent Night.”

Maybe it has something to do with — oh, I don’t know — that time I was attending midnight mass at St. James Cathedral in downtown Chicago a number of years ago, when I discovered, as I was about to leave, the wax drippings of the candle, carelessly held by the person in the pew behind me, had splattered all over my very nice winter coat.

Or … maybe it’s the way these rituals — in the safety of our 21st century Western existence – tend to “sanitize” the Christmas story and romanticize the Holy Family and the whole cast of characters at the manger.

One of my own nativity scenes at home is a collection of white porcelain figurines, trimmed in gold, serenely sitting on a shelf in the glow of my Christmas tree. So too in our churches, across the country this night, we gather under the soft glow of candlelight, our sanctuaries as much dressed in their Sunday best as the parishioners and visitors who fill them.

O little town of Bethlehem, how still we see the lie … Silent night, holy night, all is calm, all is bright …

The reality couldn’t be any further from the truth.

O little town of Bethlehem … under siege. The very land of Christ’s birth, the “Holy Land” of Muslims, Jews, and Christians, crying out in pain, amidst the violence and rubble of war. There is nothing “calm,” “silent,” or “holy” about it.

In a sermon preached just yesterday, Pastor Munther Isaac of Christmas Lutheran Church in Bethlehem in the West Bank, about 40-some miles from Gaza, speaks poignantly of the sadness, fear, and anger felt by Palestinians, lamenting the death of 20,000 of their siblings, including 9,000 children, and millions displaced. Leaving no room for ambiguity, Pastor Isaac decries the silence and complacency of the world – even the church – looking on at the ongoing violence, even as we sit here tonight:

“I was in the USA last month, the first Monday after Thanksgiving,” he reflects, “and I was amazed by the amount of Christmas decorations and lights, and all the commercial goods. I couldn’t help but think: They send us bombs, while celebrating Christmas in their land. They sing about the prince of peace in their land, while playing the drum of war in our land.”

***

In September of 1862, following the Battle of Second Manassas, American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote in his journal, “Every shell from the cannon’s mouth bursts not only on the battle-field, but in far-away homes, North or South, carrying Dismay and death. What an infernal thing war is!”

Less than a year later, Longfellow’s oldest son Charley ran away to join the Union Army, returning home only a matter of months later, after suffering a severe gunshot wound in battle.

The war hit close to home for Longfellow, but his poem “Christmas Bells,” better known by its first line, “I heard the bells on Christmas Day,” and first published in February 1865, captured the collective sorrow and trauma of a nation grappling with civil war.

And in despair I bowed my head;

“There is no peace on earth,” I said:

“For hate is strong,

And mocks the song

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!”

***

It’s all a far cry from “silent night, holy night.” Yet Longfellow’s world and the world of our siblings in the Holy Land might actually be closer to the reality of the nativity as it really was, instead of the one we’ve managed to clean up on our mantles and in our churches.

It might look more like the image on the cover of your bulletin, Tent City Nativity, depicting the Holy Family in a homeless encampment beyond the city limits.

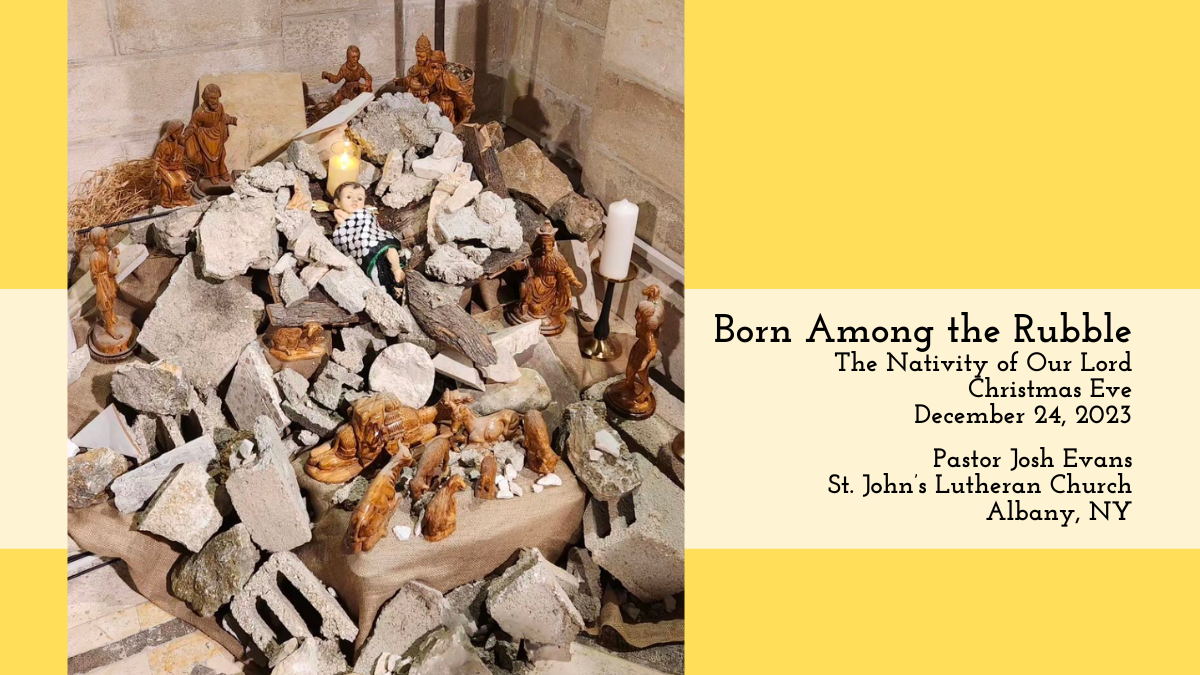

Or it might look something like the nativity scene in the chancel this year at Christmas Lutheran Church in Bethlehem, with Christ’s manger lying quite literally in a pile of rubble.

Jesus, whose family traveled from their home in Nazareth to Bethlehem – “back to where they came from” – by order of the emperor, was born under the occupation of the brutally oppressive Roman Empire.

Jesus, whose family soon thereafter was forced to flee the country out of fear for their own lives, became refugees in a foreign and unfamiliar land.

“In this Christmas season,” Pastor Isaac reminds us, “as we search for Jesus, he is to be found not on the side of Rome, but our side of the wall [in Palestine]. In a cave, with a simple family. Vulnerable. Barely, and miraculously surviving a massacre. Among a refugee family. This is where Jesus is found. If Jesus were to be born today, he would be born under the rubble.”

Born under the rubble. Not a porcelain white and gold nativity on my bookshelf, or in the soft glow of candlelight in a church on Christmas Eve.

Not removed from the rubble, but in the very midst of it: good news of great joy. Born under the rubble: Immanuel, God-with-us.

***

Longfellow’s poem certainly doesn’t deny the reality of the world he lived in, but it also doesn’t end there:

Then pealed the bells more loud and deep:

“God is not dead; nor doth he sleep!

The Wrong shall fail,

The Right prevail,

With peace on earth, good-will to men!”

Longfellow resolves to believe in the promise of peace, despite the present reality of war and violence.

It’s a sentiment shared, too, by Maya Angelou in her poem “Amazing Peace,” first read at the lighting of the National Christmas Tree at the White House in 2005:

Into this climate of fear and apprehension, Christmas enters…

In our joy, we think we hear a whisper.

At first it is too soft. Then only half heard.

We listen carefully as it gathers strength.

We hear a sweetness.

The word is Peace.

It is loud now. It is louder.

Louder than the explosion of bombs…

We tremble at the sound. We are thrilled by its presence.

It is what we have hungered for.

We, Angels and Mortals, Believers and Non-Believers,

Look heavenward and speak the word aloud.

Peace. We look at our world and speak the word aloud.

Peace. We look at each other, then into ourselves

And we say without shyness or apology or hesitation.

Peace…

To the shepherds on the outskirts of town, the angels bring “good news of great joy” – of a baby, born under occupation, far from home, in the midst of the rubble.

“Glory to God in the highest heaven, and on earth … peace.”

***

It wasn’t until five years ago, in my congregation at the time in Brookfield, Wisconsin, on my first Christmas Eve as a pastor, when this familiar ritual of lighting candles and singing “Silent Night” became one of my favorite parts of this night.

That Christmas Eve, at the very last service (of many) that night, when we all still had our candles lit and had sung the last notes of “Silent Night,” one of my pastoral colleagues leading that particular service invited us to pause, to look down at our candles, and to reflect on everything that this past year has brought us – all the joys and all the sorrows – and to look at the candles of those around us – and to rest in the grace and the community of that moment.

O little town of Bethlehem, the hopes and fears of all the years are met in thee tonight.

***

If the message of Christmas this year has any good news for us and for our hurting world, it is this: that Christ is born among the rubble.

Christ is born among the rubble and destruction in Gaza.

Christ is born among the rubble and war in Ukraine and all places torn apart by the horrors of war.

Christ is born among the rubble and violence and poverty on the city streets of Albany.

Christ is born among the rubble and despair of our own lives, among the grief we hold and that holds on to us, and among all that weighs us down.

Christ is born among the rubble, drawing near to those who suffer, those who grieve, those who cry out in anger and in fear.

***

Christ is born among the rubble.

Thanks be to God.