St. John’s Lutheran Church

25 May 2025 + Easter 6c

Revelation 21:10, 22—22:5

The Rev. Josh Evans

Revelation brings us at last through the great cosmic battle.

The empire has fallen.

Our Lamb has conquered.

Revelation brings us at last to the new Jerusalem,

a new heaven and a new earth.

Except … did you notice?

We don’t go to the new Jerusalem.

The new Jerusalem comes to us.

“Coming down out of heaven.”

Now, of course, we live in a more scientifically advanced world

than the first century,

with a vastly different understanding of cosmology and the universe

than our biblical forebears.

Heaven is not “up” – as though it’s a place we could physically reach.

But there’s a larger point here:

The new Jerusalem,

the holy city coming “down” out of heaven from God,

the new reign of God, and indeed God’s very self,

comes to us.

Radical. Incarnational. Theology.

The Word became flesh and lives among us.

The Word became flesh and camps with us –

a powerful image:

God camps among God’s people –

among God’s refugee and immigrant people,

among God’s unhoused and kicked-out people,

among God’s abandoned and tossed-aside people,

among God’s lonely and weary people.

And here in this holy city,

come “down” to earth,

in which God has set up camp,

at its center

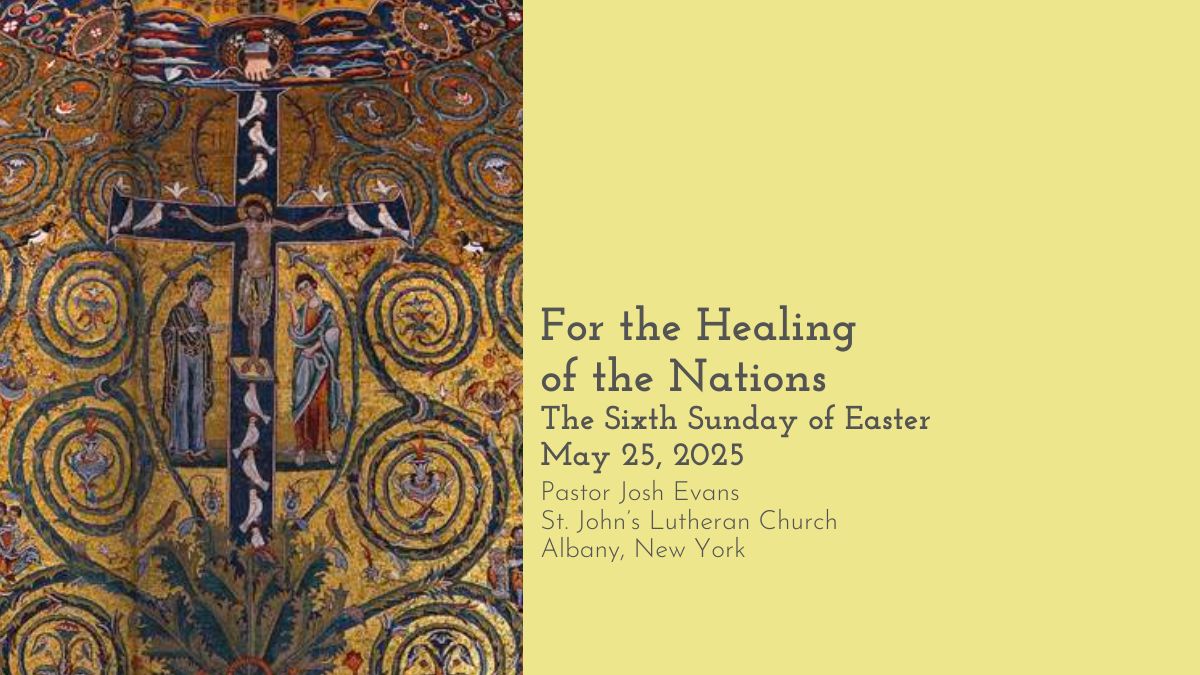

is the tree of life.

The tree of life

with leaves outstretched

for the healing of the nations.

“The image of the tree,”

writes Lutheran liturgical theologian Gail Ramshaw,

“is one of the most commonly recurring archetypes

in humankind’s religious symbol systems, cultural legends, and folktales.” [1]

From Norse and Mayan legends to indigenous Australian folklore

to the representation of royal power and national identity in the Ancient Near East,

it’s a veritable forest.

Rooted in the tradition of the Hebrew prophets,

Isaiah anticipates the restoration of the Davidic monarchy,

“the Branch of Jesse” of which our Advent hymns sing.

Even earlier, in the beginning,

Genesis recounts the creation myth

with its own “tree of life,”

planted at the center of a perfect garden

in which human beings are meant to reside…

until their hubris gets the better of them

and results in their banishment from the garden.

By Revelation,

bookending holy scripture,

the imagery is reversed,

with all the nations of the earth

beckoned around this healing tree.

Bonaventure, a 13th-century bishop of the church,

writes with his own vivid take on this imagery:

“Picture in your mind a tree whose roots are watered by an ever-flowing fountain that becomes a great and living river to water the garden of the entire church. From the trunk of this tree, imagine that there are growing twelve branches that are adorned with leaves, flowers and fruit. Imagine that the leaves are a most effective medicine to prevent and cure every kind of sickness. Let the flowers be beautiful with the radiance of every color and perfumed with the sweetness of every fragrance. Imagine that there are twelve fruits, offered to God’s servants to be tasted so that when they eat it, they may always be satisfied, yet never weary of the taste.” [2]

It’s an inviting and enticing image…

and yet one that must have felt so far from reality

for the communities receiving this letter we call “Revelation” from John of Patmos,

living in a political and social climate of tension and fear,

amid the rubble of the temple

and the holy city of Jerusalem destroyed by Roman troops,

amid the rubble of all they held dear.

John’s letter doesn’t ignore their fears,

doesn’t try to brush aside their grief,

but speaks words of encouragement and hope

into the midst of them.

Remember “Lamb Power”?

Revelation is the oxymoronic Easter gospel that reminds us:

Our Lamb has conquered,

and our Lamb will get the final word.

Rome is not the end.

This climate of fear and grief is not the end.

Instead, Revelation beckons its hearers

to imagine a future beyond their present circumstances,

beckons us to the holy city,

with its river of the water of life, bright as crystal

around the tree of life.

The late Lutheran hymn-writer Susan Palo Cherwien

puts it this way in her hymn text:

Come, new heav’n, new earth descending,

Come, O gold and radiant grace;

To our mortal world attending,

God has made a dwelling place.

Be here now the holy city:

Life abundant, joy in worth,

Words of healing, hands of pity,

Peaceful hearts and peace on earth.

Here God’s people rise beloved:

Christ has freed the heart from fear;

God’s own Spirit brightly hovers

As the reign of God appears.

Now the holy gates are opened,

Past and future pierce us through;

This, the gold of all our hoping:

God is making all things new.

Alleluia be our measure;

Alleluias mark our days;

May each breath, each deed, each pleasure

Choir to God our heartfelt praise. [3]

Notice the first word of each stanza:

Come Be Here Now Alleluia. [4]

Come be here now.

To us who are preoccupied with who’s in and who’s out,

to us who are concerned about our eternal destination,

as if that is the ultimate point of Revelation or this Christian life,

to us who get so wrapped up in the thereafter

that we lose sight of the present:

Come be here now.

“And I saw the holy city, the new Jerusalem,

coming down out of heaven from God…

And I heard a loud voice from the throne saying,

‘See, the home of God is among mortals here.

God will dwell with them here.’”

Into our climate of fear and grief,

among us who are weary and weighed down,

God’s reign has come and is coming

here and now.

God is with us here.

Our Lamb has conquered,

and our Lamb offers us peace,

not as the world gives,

but a profoundly deep and lasting sense of well-being and belovedness.

Because our Lamb has conquered … peace.

And because our Lamb has conquered,

we are emboldened to bear witness to that good news:

As leaves of the tree,

as branches of the vine,

with hands and hearts outstretched

for the healing of our communities,

for the healing of our neighbors,

for the healing of the nations,

for the healing of all of God’s beloved.

[1] Gail Ramshaw, Treasures Old and New: Images in the Lectionary (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2002), 396.

[2] Quoted in Ramshaw, Treasures Old and New, 395.

[3] Susan Palo Cherwien, Come, Beloved of the Maker (Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress, 2010), 22.

[4] Cherwien, 119.